Having a sick child can be a nerve-racking time. Having a sick infant is even scarier as you, as a parent, feel helpless. In these times, caregivers turn to the experts in medical centers to help. But, unfortunately, a hospital can’t always help before it is too late.

Having a sick child can be a nerve-racking time. Having a sick infant is even scarier as you, as a parent, feel helpless. In these times, caregivers turn to the experts in medical centers to help. But, unfortunately, a hospital can’t always help before it is too late.

In June of 2012, 13-month-old Landon Lee was transported via ambulance to Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center (OLOL) due to vomiting and respiratory distress. Landon was treated in the emergency room by Dr. Boudreaux, where he was determined to have cardiac issues. He was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at OLOL. Later the same morning, Landon Lee was transferred via helicopter to Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans to be placed in an Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation unit (ECMO). Within an hour of arriving at Ochsner, Landon died. The autopsy determined 13 month-old Landon passed from cardiomegaly or an enlarged heart.

Landon’s mother filed a lawsuit on her behalf and for her deceased son against both OLOL and Dr. Boudreaux, the pediatrician and emergency room physician who treated Landon at OLOL. Lee asserts in her claim that Boudreaux and OLOL failed to properly care for and treat her son while at OLOL. Along with the allegations in her lawsuit, Lee attached an affidavit from Dr. Meliones, a board-certified pediatric cardiologist specializing in pediatric critical care, to support Ms. Lee’s negligence claim.

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Louisiana Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Sickness often begets a doctor’s visit, and sometimes severe illness calls for a trip to the emergency room. So when parents, David Pitts, Jr. and Kenyetta Gurley, arrived at Hood Memorial Hospital in Amite City, Louisiana, with their daughter, Lyric, it’s likely neither expected to leave there without their daughter’s health restored.

Sickness often begets a doctor’s visit, and sometimes severe illness calls for a trip to the emergency room. So when parents, David Pitts, Jr. and Kenyetta Gurley, arrived at Hood Memorial Hospital in Amite City, Louisiana, with their daughter, Lyric, it’s likely neither expected to leave there without their daughter’s health restored. Deadlines matter in all areas of life, but in the legal world, they can determine whether a lawsuit will move forward or even get started. In Louisiana, a prescriptive period is a window of time for legal action to be brought and enforced. Depending on the kind of claim, the prescriptive period may be longer or shorter than you think.

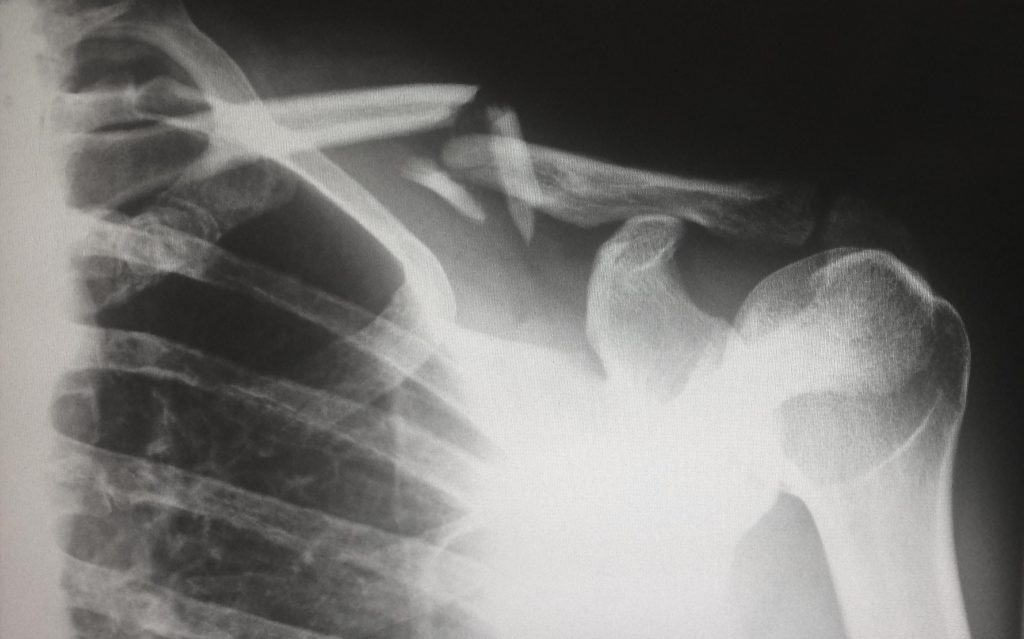

Deadlines matter in all areas of life, but in the legal world, they can determine whether a lawsuit will move forward or even get started. In Louisiana, a prescriptive period is a window of time for legal action to be brought and enforced. Depending on the kind of claim, the prescriptive period may be longer or shorter than you think. Medical procedures are never an enjoyable process. However, the process becomes even more miserable when recuperation is delayed because of infections. Darrin Coulon found himself in this situation after receiving shoulder surgery in 2011 from Dr. Mark Juneau at the West Bank Surgery Center. His recovery became even more difficult as he navigated the complex procedural requirements of filing a medical malpractice claim.

Medical procedures are never an enjoyable process. However, the process becomes even more miserable when recuperation is delayed because of infections. Darrin Coulon found himself in this situation after receiving shoulder surgery in 2011 from Dr. Mark Juneau at the West Bank Surgery Center. His recovery became even more difficult as he navigated the complex procedural requirements of filing a medical malpractice claim. Lawsuits are filed every day. However, not all of these lawsuits are worth the attention of the courts. Courts are already swamped with dozens and dozens of cases on their dockets and they cannot afford–both monetarily and temporally–to hear every case that comes to their courtrooms. As a result, courts allow parties to file a motion for summary judgment, which allows courts to drop a lawsuit if there is no issue of material fact among the parties.

Lawsuits are filed every day. However, not all of these lawsuits are worth the attention of the courts. Courts are already swamped with dozens and dozens of cases on their dockets and they cannot afford–both monetarily and temporally–to hear every case that comes to their courtrooms. As a result, courts allow parties to file a motion for summary judgment, which allows courts to drop a lawsuit if there is no issue of material fact among the parties.  Medical malpractice claims often present complicated issues involving hard to understand medical principles. Such lawsuits can become further complicated by questions of whether hospitals, in addition to the doctors themselves, can be held liable for a failure to act that results in a patient’s death. This is the question faced by parties in a lawsuit alleging medical malpractice and negligence that followed the death of a patient initially treated at the Richardson Medical Center Hospital (“RMC”) in Rayville, Louisiana.

Medical malpractice claims often present complicated issues involving hard to understand medical principles. Such lawsuits can become further complicated by questions of whether hospitals, in addition to the doctors themselves, can be held liable for a failure to act that results in a patient’s death. This is the question faced by parties in a lawsuit alleging medical malpractice and negligence that followed the death of a patient initially treated at the Richardson Medical Center Hospital (“RMC”) in Rayville, Louisiana.  Maybe you’ve been there. Lying on a cold surgical table. The anesthesiologist places the mask over your face and says to count backwards from one hundred. “100…99…98…” Most people don’t remember much after that. But imagine waking up from a procedure and discovering that you have no feeling in your arm. Unfortunately, that’s what happened to Jason Dunn, who underwent a hemorrhoidectomy at Christus St. Francis Cabrini Surgery Center in Alexandria, Louisiana in 2012.

Maybe you’ve been there. Lying on a cold surgical table. The anesthesiologist places the mask over your face and says to count backwards from one hundred. “100…99…98…” Most people don’t remember much after that. But imagine waking up from a procedure and discovering that you have no feeling in your arm. Unfortunately, that’s what happened to Jason Dunn, who underwent a hemorrhoidectomy at Christus St. Francis Cabrini Surgery Center in Alexandria, Louisiana in 2012.  The statute of limitations, by definition, is the timeframe set by a state or federal legislative body in the creation of a law which governs when a party must file a claim to enforce his or her right or seek redress after injury or damage. The statute of limitations on personal injury claims varies from state to state. The standard statute of limitations for personal injury cases is three years from the day the injury or damage, in which the claim arises, took place. Mr. Landis J. Camp’s appeal from the Twenty-Fourth Judicial District Court to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the State of Louisiana against Dr. Chris J. DiGrado and Lammico Insurance Company exemplifies the vital importance of filing a personal injury claim within the statutory period of a given state.

The statute of limitations, by definition, is the timeframe set by a state or federal legislative body in the creation of a law which governs when a party must file a claim to enforce his or her right or seek redress after injury or damage. The statute of limitations on personal injury claims varies from state to state. The standard statute of limitations for personal injury cases is three years from the day the injury or damage, in which the claim arises, took place. Mr. Landis J. Camp’s appeal from the Twenty-Fourth Judicial District Court to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for the State of Louisiana against Dr. Chris J. DiGrado and Lammico Insurance Company exemplifies the vital importance of filing a personal injury claim within the statutory period of a given state. Medical Malpractice lawsuits can be extremely complicated and fact-specific. The general Louisiana law requires claims to be brought within one year of treatment. The Louisiana law also distinguishes liability based on intentional actions from negligent actions. The following case illustrates how in-depth a medical malpractice claim can become.

Medical Malpractice lawsuits can be extremely complicated and fact-specific. The general Louisiana law requires claims to be brought within one year of treatment. The Louisiana law also distinguishes liability based on intentional actions from negligent actions. The following case illustrates how in-depth a medical malpractice claim can become.